THE THEATRE OF ART

Delacroix’s "Medea About to Kill Her Children (Medée furieuse),” 1838, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille. This painting offers a staggering contrast to Greek theatre, where the violence occurs offstage and is reported by a Messenger. Here Delacroix shows us something audiences have never seen: Medea about to claim her children’s lives. To see the unthinkable act, Medea’s madness, and the children’s fear was almost more than I could bear. Such is the emotional realism of Delacroix.

I first experienced the singular glory of Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) at Philadelphia Museum twenty years ago. In the years since I’ve continued to thrill at his name and the occasional sighting, but lost touch with the source of my original awe and confess to wondering if it wasn’t partly the ardor of a nineteen-year-old.

When I got back from The Met’s newly opened Delacroix on Sunday—the first full retrospective mounted in North America, organized with the Louvre—I was as rapturous as the first time, drunk on Delacroix. Along for the ride, my three-year-old had blessedly passed out on arrival and was parked her between galleries as I inhaled the best museum hour I’ve had in years. It took about three seconds of revisiting the master’s wildly theatrical works—all tangled bodies, black eyes and teal seas—to remember why I had fallen in love.

Delacroix’s “The Bride of Abydos (Selim and Zuleika),” 1857, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. Inspired like many of his paintings by the writings of Lord Byron, we learn from the placard that it is “Set in the Dardanelles in Ottoman Turkey, it depicts the pirate Selim attempting to rescue his lover Zuleika from the harem of the pasha Giaffir. After sounding the pistol to alert comrades waiting to rescue them offshore, Selim inadvertently reveals their location to Giaffir’s approaching posse, thereby dooming the couple.”

Adding to my heightened appreciation for Delacroix’s “belief in the expressive power of painting” is an impressive new one-woman show about Artemisia Gentileschi, an Italian Baroque Painter (1593-1653), out-shadowed by Caravaggio (1571-1610) in spite of her comparable skill. Artemisia’s Intent, devised by The Anthropologists, directed by Melissa Moschitto and starring the always compelling Mariah Freda, sets the record straight about the painter’s genius, and what it cost her.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes,” between 1623 and 1625, on display at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Moschitto took a pilgrimage to see this masterpiece last January and it inspired the opening scene of the play.

Among the show’s many virtues, Artemisia improved the way I see the action—the drama—of art. By contorting herself into her subjects’ suffering, she shows the painter as method actor dependent on believing their material in order to sell it. For both Artemisia and Delacroix, the truth was all-important. On being called a Romantic Delacroix wrote, “If by Romanticism one means the free manifestation of my personal impressions, my aversion to the models copied in the schools, and my loathing for academic formulas, I must confess that not only am I Romantic, but I was so at the age of fifteen.”

Artemisia was raped at the age of seventeen, which also meant she was “damaged goods.” After a harrowing but impressively executed rape scene and being prejudicially cross-examined in a way that feels morbidly contemporary, Artemisia’s dedication to truth becomes a matter of life and death:

You can ask me a million questions—I’m never going to say anything different. I never have said anything different. I say this, that everything I have said is the truth, and that if it were not the truth I would not have said it.

(Approaching the ropes hanging center stage)

Yes, sir. I am ready to confirm my testimony even under torture.

The omni-talented Mariah Freda as Artemisia. Photo by Jody Christopherson.

The actress in this next painting is Greece personified. From the painter who said, “The artist who aspires to perfection in everything achieves it in nothing,” it’s obvious Delacroix aspired to perfection. He had me at “Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi,” one of the first works on display:

Delacroix’s “Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi,” 1826, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux. From the placard, “This painting was inspired by a nearly year-long resistance mounted in 1825 by the residents of the Greek city of Missolonghi against Ottoman troops…The siege fostered widespread sympathy in France for Greek independence… The painting was included in an 1826 exhibition held as a benefit for the Greeks.”

With Greece still on my mind—my Acropolis tour guide’s heated words about the Turks, the statue of Bouboulína in Spetses—I was staggered by this painting’s passionate expression of European values over barbarism. The French artistic elite were invested in Greek independence, a cause célèbre of post-Revolutionary France.

Delacroix is a painter of many words; he wrote prolifically and eloquently with profound introspection. In 1830 he published an essay on Michelangelo in which he wrote, "I picture him late at night, struck with fear at the spectacle of his creations, rejoicing in the secret terror that he wanted to awaken in men's souls...It was then the expression of a profound melancholy, or perhaps his agitation, his dread, in thinking of his future life: the regrets of old age, fear of an obscure and frightening future." These could be the words of a playwright or director deep in character development. Twenty years later Delacroix completed his one-scene “play”:

Delacroix’s “Michelangelo in His Studio,” 1849-50, Musée Fabre, Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole.

Delacroix tested himself methodically and patiently throughout his four-decade career, seeking first excellence, then fame, then truth. At a time when the mutual reverence between poets and painters was ardent, the literary canon gave Delacroix scenes for many of his masterpieces.

Delacroix’s “Hamlet and Horatio in the Graveyard,” 1839, Musée de Louvre, Paris. From the gallery writeup entitled Drama and Monumentality: “The paintings in this gallery…demonstrate the fecundity of Delacroix’s imagination at midcareer. [His] art, which had always relied on a keen sense of drama…thus became infused with a new grandeur as well as a deep reflectiveness that came with age.”

I learned the word ekphrasis at my alma mater, St. John’s College, while discussing the poet W. H. Auden’s gut-punching masterpiece Musée des Beaux Arts. In loosest terms it means any piece of art that takes another as its subject. Artemisia’s Intent the play and Delacroix the exhibit are both shrewdly written testaments to the power of artistic exchange. Doubling down on creative impact, they give you more than the beauty of a single medium—and history lessons to boot—for the price of a ticket less than lunch. See them.

Artemisia’s Intent can next be seen at Scranton Fringe and Delacroix runs through January 6. #EugeneDelacroix #ExpoDelacroix #ArtemisiasIntent #WhatAWomanCanDo #WorkLikeAMother #ArtistMom

Mariah Freda as Artemisia. Photo by Jody Christopherson, 2018.

“Susanna and The Elders,” 1610, Schloss Weißenstein collection, Pommersfelden, Germany. Her first painting that is signed by her but was commonly attributed to her father, Orazio Gentileschi.

Woman according to Delacroix. I think Artemisia would approve. “Female Academy Figure: Seated, Front View (Mademoiselle Rose),” 1820-23, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie.

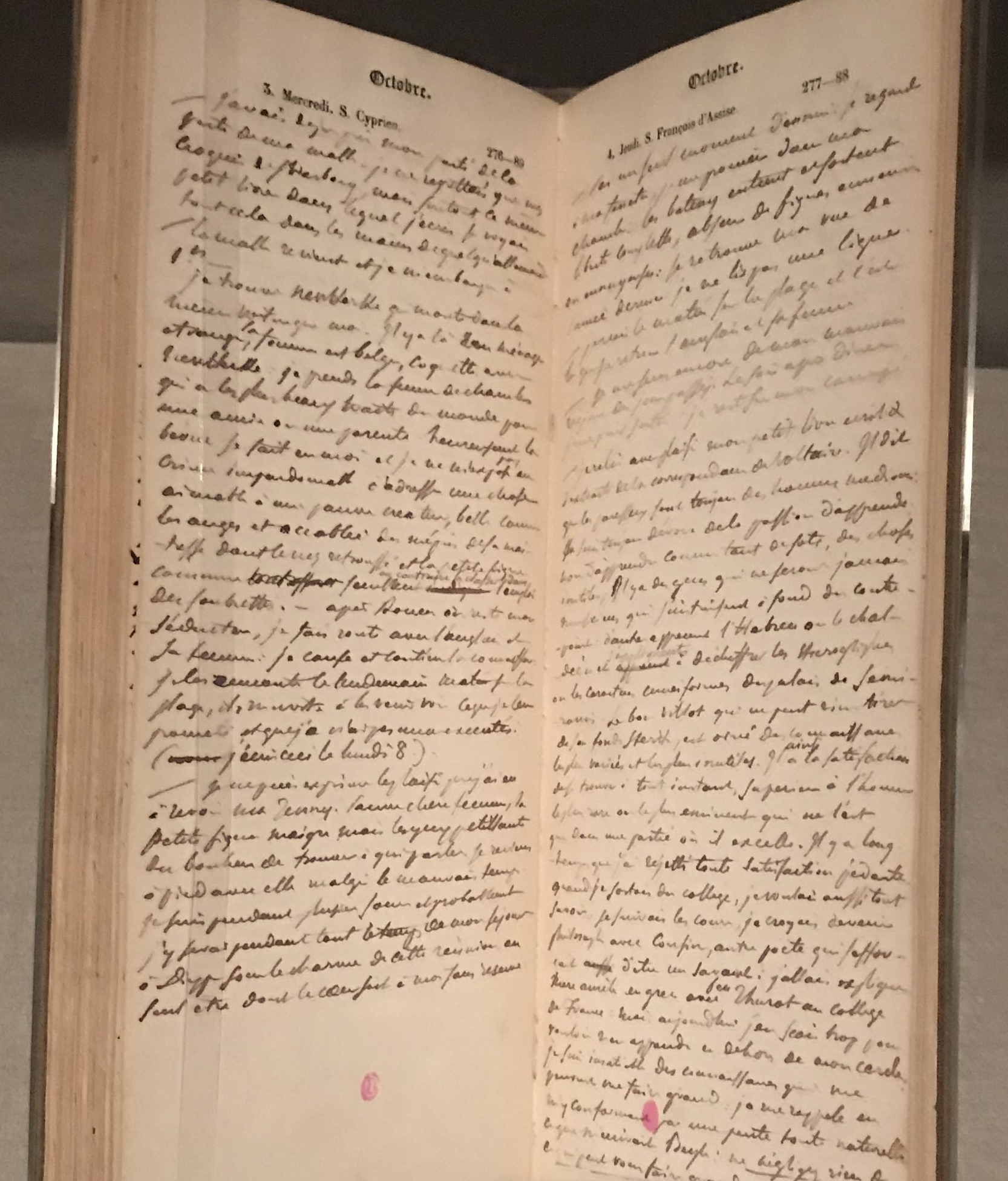

Delacroix’s journal. From the exhibit, “The artist’s most important written work is his Journal, which he kept from 1822-24 and then again from 1847 until he died in 1863. A highly personal record of the era, it served as a means for gaining self-knowledge and documenting his artistic convictions.”

![Delacroix’s “Hamlet and Horatio in the Graveyard,” 1839, Musée de Louvre, Paris. From the gallery writeup entitled Drama and Monumentality: “The paintings in this gallery…demonstrate the fecundity of Delacroix’s imagination at midcareer. [His] art, …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5321dd5ee4b002087ac245bb/1537627597751-D9GEBHJAUEHVL9CVCEIL/Hamlet.jpg)