ADDICTED TO LIT: The Vital Decadence of Great Books

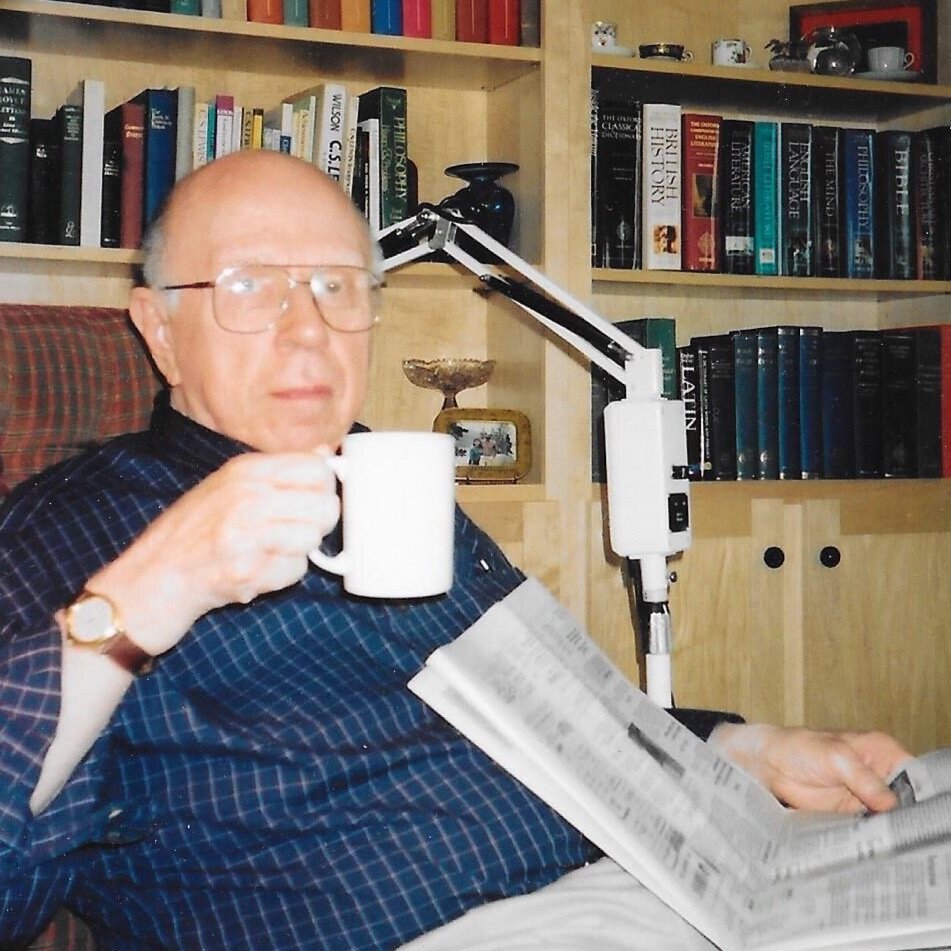

My grandfather Roger Forseth and Sinclair Lewis, imaginary friends in a relationship I describe in my intro to our book.

On Tuesday, September 17, 2019, I had the honor of delivering a talk about my book of my grandfather Roger Forseth’s writing, Alcoholite at the Altar, to a body of St. John’s College alumni. I was humbled and invigorated by the many questions and interest in our material: the study of the writer and addiction. The following is adapted from my talk:

Thank you so much for having me here today and Dan [Van Doren] for the kind intro. It’s been far too long since I attended an alumni event or seminar, which makes it all the nicer to be back. Congratulations to the class of 2019, and to all recent graduates living in New York, I look forward to meeting and hearing how the City is treating you!

Fifteen years ago this month I moved to New York straight from Santa Fe. I miss New Mexico and St. John’s no less today than when I pulled out for the last time onto Highway 35 and drove myself home to Minnsconsin (I’m from the border) before taking a one-way flight to New York town.

In my fifteen years since completing the Western Classics Graduate Institute program, which some of you may call “St. John’s Light,” I’ve done the restaurant thing, the copyediting thing, the wedding thing, the beauty industry thing, the parenting thing…and it’s all felt like a whole lot of work compared to the Great Books thing.

Because for those who love it, and by it I mean the the brain-tickling practice of reading Great Books and discussing them with others who care about the questions they ask, to do so is a luxury, a form of entertainment, a dare I say decadence, that real life in this pay-your-way world doesn’t always leave room for.

Those of us here, however, know that rather than merely a luxury—let’s call it Great Booking—is a vital and necessary practice that life is so much emptier and scarier without. One that calls to mind the William Carlos Williams quote, "It is difficult/to get the news from poems/yet men die miserably every day/for lack/of what is found there."

In recent years, the project of publishing my grandfather Roger Forseth’s writings, the topic of my visit tonight, has brought me closer to my St. John’s roots than anything since I left. And on reflection, I realize I probably went to St. John’s because it brought me closer to him.

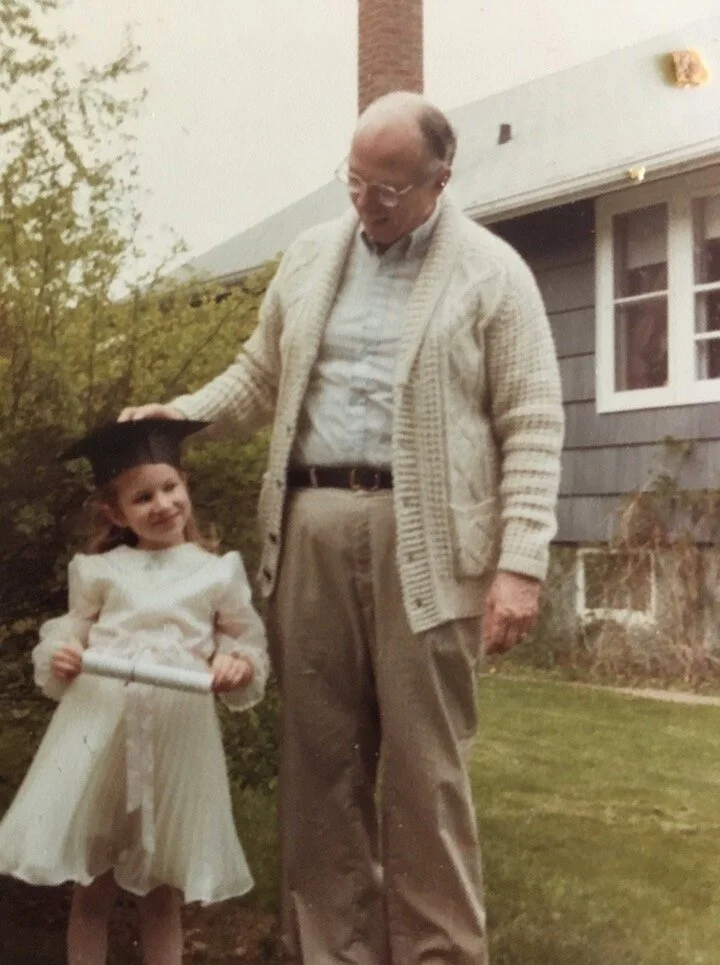

Kindergarten graduation, 1985. He always took me seriously and that, to borrow from Frost, has made all the difference.

Briefly about Him. My grandfather was an English professor and scholar out of Carleton and Northwestern who eventually became a tenured prof at the lesser-known University of Wisconsin-Superior. A recovering alcoholic, sober from the age of 47 in 1974, he dedicated his career to the study of the writer and addiction, particularly Sinclair Lewis, and helped pioneer his field with the publication of a magazine called Dionysos: The Journal of Literature and Addiction, which ran from 1989 to 2000.

In 2014, scholars in England stumbled across copies of Dionysos at the British Library and gained permission from my grandfather to digitize them. This inspired Grandpa to ask me, who had worked in theatre publishing, to compile his essays into book form.

Two years after he passed away, in December of 2016, last summer I published his book, Alcoholite at the Altar: The Writer and Addiction. It includes nineteen essays and talks, an intro and afterword by me, and an epic Index by the masterful Paula Clarke Bain that is about as Great Books-y as it gets.

And now that the book is complete, where it belongs on the All-Mighty Market is the question. The irony has been far from lost on me that I am often speaking about this project with or to those with a drink in hand. This irony goes so far that a concurrent project of mine is a cocktail book for my husband’s restaurant! I am fearful of Alcoholite’s coming across as a buzz kill, for it’s so much more fun than that. It is, after all, an ode to literature first and addiction second. For anyone who has marveled at Lewis, been seduced by Fitzgerald, heartbroken by O’Neill, or blown away by Hemingway, no pun intended, these essays will take you deep into their lives and works while providing a fascinating understanding of how drink affected, infected, and sometimes even perfected their words.

Now I will let my grandfather speak for himself. In this excerpt from the book’s title piece, Alcoholite at the Altar: Sinclair Lewis, Drink, and the Literary Imagination, he likens the alcoholic to the tragic Greek hero Philoctetes who, with “his foot diseased and eaten away with running ulcers,” recalls the incurable affliction that the unrecovered alcoholic repeatedly endures. Philoctetes, possessed of superhuman powers, is like a great artist whose disease is tolerated because of his gifts.

“Philoctetes on the Island of Lemnos” by Guillaume Guillon-Lethiere. Starring in four eponymous Greek tragedies, of which only Sophocles’ exists, Philoctetes was a Greek hero of equally great power and injury. In possession of Heracles’ bow and poison-tipped arrows, he also suffered an incurable and offensive foot injury, making him something of a poster child for life’s mixed bag.

The subject of alcoholism and the writer—especially the twentieth-century American writer—has received massive anecdotal attention, but little serious analysis. Critics cite an article by psychiatrist Donald Goodwin that…“Alcoholism is unevenly distributed among groups. More men than women are alcoholic, more Irishmen than Jews, more bartenders than bishops. The group, however, with possibly a higher rate of alcoholism than any other consists of famous American writers.”

Most of the critical literature on the writer and alcoholism is no more serious or enlightening than [this] generalization. [Critics] string together a series of incidents that in the main portray the writer variously as a reverent or heroic or pathetic drunk. Such facile, unproductive characterizations do not advance the serious assessment of the effect addiction has on the art of particular American writers. And when Mark Schorer [Sinclair Lewis’s own biographer] quotes an anonymous punster on Lewis—“‘an alcoholite at the altar’”—the flippant witticism evokes yet another familiar image of the writer and liquor: an image of artistic creation through alcoholic inspiration…

…The romantic notion that alcohol was both an aphrodisiac and a creative stimulant persists in the face of personal horror…I wish to emphasize strongly, however, that it remains to be seen whether drink is necessarily bad for art—even where the artist is a compulsive drinker. A distinction must be made between the devastation of personal lives and the realizations of art. Dick Diver in Tender Is the Night, Julian English in Appointment in Samarra, and the Consul in Under the Volcano are marvelous creations that could only have been drawn by alcoholics. The personal calamity is sublimated into the positive creative act.

In a famous if much criticized essay by Edmund Wilson, Wilson describes Philoctetes as the “victim of a malodorous disease which renders him abhorrent to society, periodically degrades him, and makes him helpless but who is also the master of a superhuman art which everybody has to respect and which the normal man finds he needs.” Wilson’s observation helps to keep matters in perspective by focusing on the serious art, not the sensational life. Truman Capote once said, with his characteristic exaggeration, that “I don’t know a single writer…who isn’t an alcoholic,” but more revealingly he also wrote, “I’m an alcoholic. I’m a drug addict. I’m homosexual. I’m a genius.” Capote’s stylish anguish epitomizes the problem before us.

From Capote’s own book of Brooklyn photography, published in 2014. Complement this with Vanity Fair’s 2006 publication of Capote’s last written words, a reminiscence about meeting Willa Cather as a young man in the winter of 1942.

In my grandfather’s subsequent analysis of letters by Lewis and his two wives, Lewis’s drinking habits are heartbreakingly revealed as so preoccupying and calculated as to be quite outside of any consistent control. The section concludes:

Sinclair Lewis was, then, all his adult life afflicted with a primary, progressive, incurable disease that was never treated and never accepted—by him, by his family, by his friends, and ultimately by his public. But a just determination of the achievement of Lewis must begin with this acceptance. The two vital activities of his life were, bluntly, drink and work. The precise ways these two activities affected each other and therefore his craft were profound, if elusive.

In the last year of his life Lewis himself tells us how he feels about his art, and these feelings are as much a symptom of his alcoholism as they are of his dedication to his craft.

“I wanted to write, and I’ve worked like hell at it, and the whole of Sauk Center [sic] and my family and America have never understood that it is work, that I haven’t just been playing around, that this is every bit as serious a proposition as [Lewis’s brother] Claude’s hospital. When you said that Claude did not want to hear my lecture… you set up all the resentments I have had ever since I can remember.”

There it is: the unresolved anger of a lifetime.

That line of my grandfather’s, “the unresolved anger of a lifetime,” lands like a punch. After all Lewis’s successes, millions of dollars and books sold, the first American Nobel for Literature in 1930, what painful resentments he lived with, what lack of serenity and haunting insecurity accompanied him to the grave.

So why, to paraphrase my grandfather, must a just determination of Lewis’s achievements begin with the acceptance that he drank and worked a lot and that these two activities profoundly affected each other?

For many readers in the non-academic literary community, it’s not necessary to understand biography, nor should biography—the sweetness of Van Gogh, the sins of Gauguin—skew the perception of a work for good or for bad. You either like it or you don’t; the critics praise or pan it according to their metrics. But I think we all know what it feels like to love a work of art, and sometimes its maker, with an investment that goes deeper than intellect. A book can change our thinking and lives, its characters enter our imagination and memories like real people we’ve personally known. Certainly for my grandfather, and for anyone who has experienced this phenomenon, it can increase joy to know more about the genesis of something you love. In the end, of course, we learn less about our subjects than ourselves.

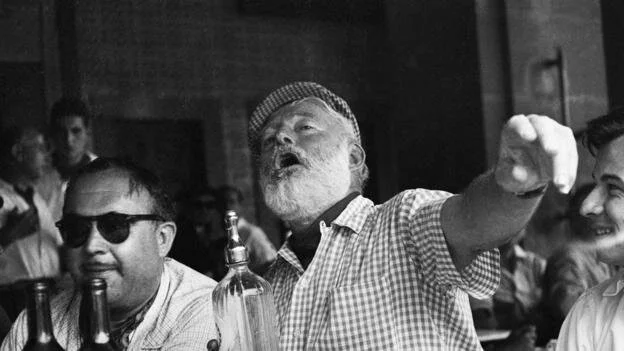

As an English professor and recovering alcoholic, it was especially profound for my grandfather to understand how some of our greatest writers functioned with the disease he shared. In examining this, he reveals much about America and its literature, including the style and snobbery that expose the Roaring Expats—Hemingway, Pound, Joyce, Stern—the Midnight in Paris group to reference Woody Allen’s film, speaking of unflattering biography—as the pettiest of cliques, begrudging Lewis’s right to write his own way.

Lewis, as handsome as he ever looked. He must have loved this photo, as do I, for it gives an idealized moment to the man the expats mocked. Certainly no one should have dismissed the author of these luminous words, from the opening of Main Street. Photo credit: Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

In an essay from 1997 “Main Street and Paris: Can You Go Home Again?” my grandfather examines Lewis’s other great and unresolved conflict, Midwestern versus cosmopolitan ideals, to which I keenly relate:

For all his peripatetic cosmopolitanism, Sinclair Lewis throughout his life returned home, to the Midwest, to Minnesota, to Sauk Centre. And though his nature did not allow him to stay long in one place, his deep attachment to the land and people of his origin prevented his becoming a genuine “Lost Generation” expatriate. Carol Kennicott [the heroine of Main Street] finally—not Paris—was his mistress: died in Rome, buried in Sauk Centre, was his symbolic epitaph…

…Lewis’s celebrity following the immense success of Main Street led to a popular and fashionable preoccupation with the behavior of the man himself; it is not an exaggeration to observe that Sinclair Lewis was the first major American author whose personal “style” received as much attention as his work. Lewis the celebrity began to overshadow Lewis the artist [and both], as we shall see, were to be disparaged by the expatriate community.

[Lewis’s] simple, relatively ordinary views of style sharply contrast with the theory of style developed, for example, by Henry James…James and his successors were, of course, to carry the day. Gertrude Stein and Hemingway, not Lewis and Dreiser, were to define the Modernist style, both as literary form and as “life style.” There was no place there for the man from Main Street. And the criticism of Lewis by the expatriates, when it was not focused on his person, was directed at his traditional literary method.

The flow of American writers, artists, and intellectuals to Europe after the Great War seemed endless. Humphrey Carpenter, in Geniuses Together: American Writers in Paris in the 1920s, lists over fifty such figures in his biographical appendix—and he includes only the principal players. Lewis is not included, and rightly so, for to the “geniuses” he was the enemy. It is not hard to see why: to succeed in your own country, it seems, is to fail in Montparnasse.

The characters in my grandfather’s pantheon: Lewis as Odysseus, ever-seeking home, with his own biographer as mortal enemy; Hemingway as jealous genius and bully drunk; Fitzgerald and his editor-therapist to whom he confesses regret; O’Neill—who did sober up, and dramatized addiction as family disease; the poor poets Berryman and Dylan who were utterly helpless at Dionysos’ altar; and Alexander the Great who more literally worshipped Dionysos and, this was news to me, seems to have died of alcohol poisoning. These and many more stand in for every victim of addiction, becoming calls for sympathy, permission slips for sobriety, and above all, inspiration to, if I may quote another Lewis—one C.S.—to “read to know we’re not alone.” My grandfather knew that more than any course of treatment, courses in Great Books and Good Books and even So-So Books—he devoured mysteries—are a talisman against unresolved anger, against unresolved fear, against despair of every kind.

Hemingway, who my four-year-old daughter would certainly call a “meaner,” served as a great way to talk about how or if to separate a great work of art from a maligned maker. This is particularly apt in the era of Me Too, when it seems impossible to unring the bells of all we’ve heard—even if we wanted to.

Have I found this book’s place? Perhaps. My grandfather’s analysis of the drunk—of the alcoholic—is an analysis of the human condition, of the tight rope we walk to stay on our feet, a rope that can get thinner with a drink in hand, even if the drink can help you reach the other side. It’s an acknowledgement of what it takes to live, and especially to create, even when you know that life’s a gift. My grandfather teaches us that understanding the addict with sympathy and tolerance in lieu of judgment and disgust, allows us to live with more patience, more serenity, and more humility in the knowledge that there but for the grace of God, or should I say Dionysos, go I.

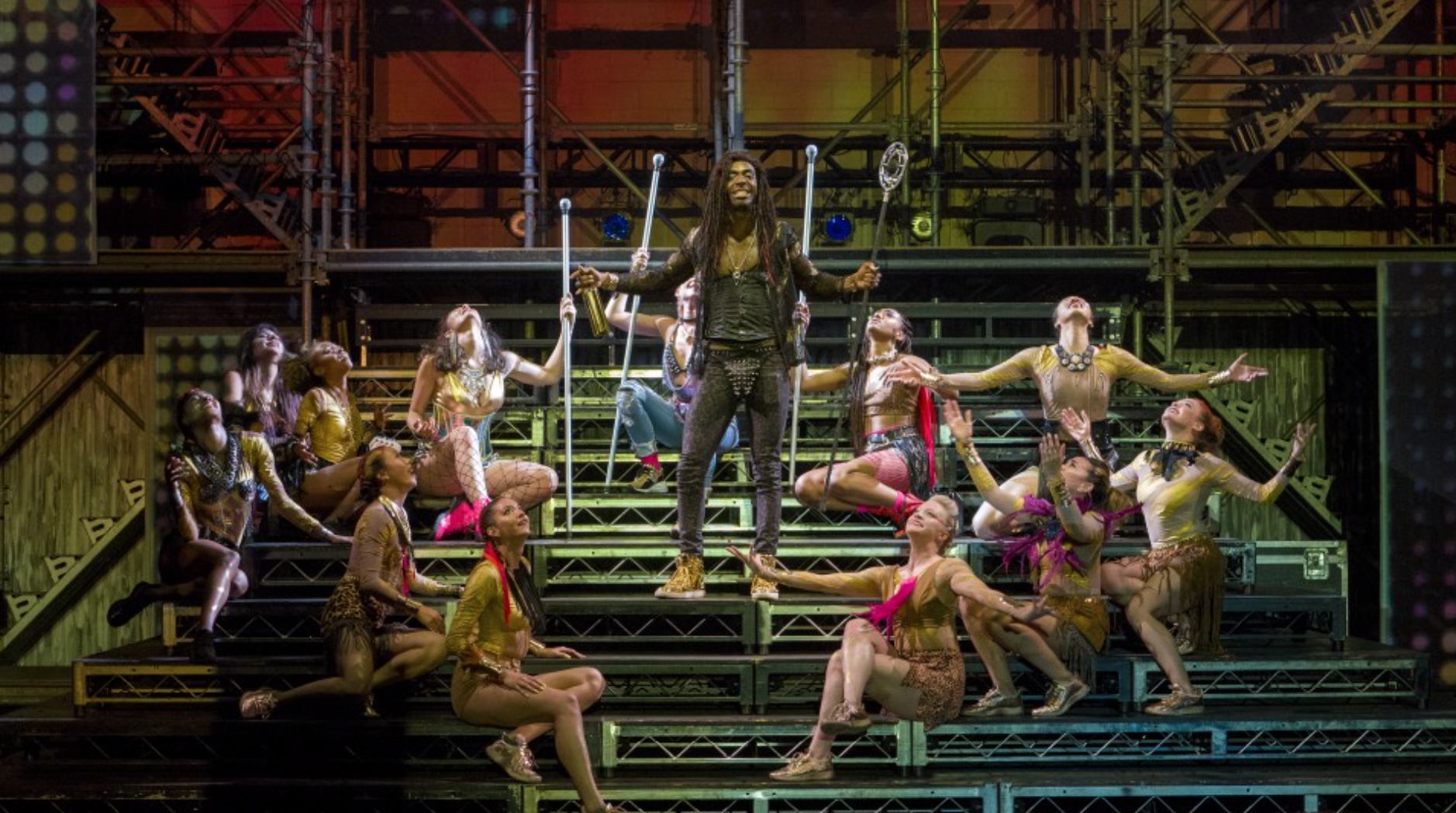

The Classical Theatre Harlem’s 2019 production of The Bacchae, the most festive of Greek tragedies, as translated from Euripides by the always accessible, faithful, and entertaining Bryan Doerries. Photo by Sara Krulwich/The New York Times.

The Santa Fe campus of my graduate alma mater, St. John’s College. The best money I’ve ever owed! I believe the school’s golden era lies ahead as its offspring shine in a job market hungry for professionals who’ve read and pondered well. Note this thrilling piece on a newly discovered work by John Locke at the Annapolis campus! Photo by Ben Gibbs.