TO LIFE

To Dust wife-husband producer team Emily Mortimer and Alessandro Nivola bookend the film’s stars, Géza Röhrig and Matthew Broderick, alongside our friend Shawn Snyder, who directed and co-wrote the film.

Over the past five years I’ve had the honor of watching my friend Shawn’s first film grow from the rib of a strange idea to a creation so complete it won two awards at Tribeca, was purchased by Good Deed Entertainment and Sony Pictures, and opened nationally in theatres on Friday.

Each To Dust milestone has been a vicarious thrill, from the 100K Sloan Foundation grant for a “science-based film” that inspired its far-fetched premise, to finding its dream producers in Emily Mortimer (Mary Poppins) and Alessandro Nivola (Disobedience), its dream protagonist in Géza Röhrig (Son of Saul), and ultimately its dream co-star in none other than Matthew Broderick.

As Shawn is the first to say, To Dust’s existence is something of a miracle. The making of any film is a long obstacle course and his unlikely story called for additional leaps of faith. That a mourning Hasid (Shmuel/Röhrig) would become so obsessed with the fate of his late wife’s remains he would consult a “goy” science teacher (Albert/Broderick) and that together they would re-create the timeline of decay with a pig corpse, takes odd, and odd couple, to a new level.

Matthew Broderick as Albert, a community college science teacher, and Géza Röhrig as Shmuel, a widowed Hasidic cantor, deliberating in their pig grave.

But once you buy in, the film begins to lay its uncomfortable gifts at your feet. Alternately heartbreaking and hilarious, the graveside scenes invite you to the underworld in a way that mitigates fear. It’s a judgment-free zone for the painful curiosity that can surround the fate of body no longer animated by soul. I first read To Dust before losing my grandpa in 2016 and Shawn’s story was with me as I grappled with what it meant to have and have not in the days between death and burial—he was still there, until he wasn't.

On the cathartic-comedic side, Albert and Shmuel’s absurd exchanges are cultural gold and sweet relief, especially at a time when open communication can seem stifled by fear. As the extremes of an Orthodox Hasid’s profound faith and sinful self-questioning collide with the woes of a faithless, purposeless American, the stage is well set to tickle our funny bone. Take this after Shmuel drags Albert to the site of the first pig burial (yes, there’s more than one):

He [Albert] considers the pig corpse.

ALBERT (CONT’D) Look. First of all. I don't condone any of this. Second. Three feet. Really? That's all. -- Where did he come from?

SHMUEL Szechuan Delights. In Rockland.

ALBERT Up on Route 87? Shmuel nods. Hm. - They do good Dim Sum. -- Well. Shmel. It's no good. Our friend here was probably frozen, shipped, thawed. Most certainly gutted and cleaned. You won't get a comparable decomp here.

SHMUEL It's no good?

ALBERT No. And, with all due respect to your wife, I imagine she was larger than...

SHMUEL Yes.

ALBERT How did she die?

SHMUEL Cancer.

ALBERT I’m sorry. --- So she was probably pretty withered by the end?

SHMUEL Yes.

ALBERT Terrible disease. --- And she was buried how long after?

SHMUEL 13 Hours.

ALBERT You guys don't waste anytime, huh? - - This just. Shmel. This just isn’t right. If. IF. You were gonna go about this proper. You’d need an ungutted, an uncleaned, and freshly deceased pig. Teeming with bacteria. But no blood loss. Can’t imagine your wife was buried straight in the earth?

SHMUEL No.

ALBERT No.

SHMUEL In shrouds.

ALBERT Just shrouds?

SHMUEL And a coffin.

ALBERT A Cadillac?

SHMUEL Excuse me?

ALBERT Was it velvet lined? Souped up? Keepsake compartments? Little drawer for snacks, in case she gets hungry?

SHMUEL No. We don’t do that. Wooden. Pine. With three small holes. In the bottom.

ALBERT Holes in the bottom?

SHMUEL So that she touches the earth. --- To dust.

ALBERT Weird. --- If you'd have gotten me a pig like your wife, no offense. And buried her like a Jew. No offense. Then maybe we'd be cooking. But this here, is, just, uh - This is a mockery of science.

Throughout To Dust language serves as both symbol and excavator of cultural divide. Shawn and co-writer Jason Begue reveled in identity wordplay, from subtle Yiddishisms to shameless slapstick, and have spoken of testing how much humor the story could hold. One of my favorite moments derives from Shmuel’s name (properly pronounced Shmooelle), which Albert spends the first three-quarters of the movie butchering Shmel (rhymes with smell). When Shmuel is finally moved to correct him, an important barrier is lifted between these most opposite of men.

Matthew Broderick as a divorced community college science teacher who has “accepted his ceilings.”

In spite of its surrealism, To Dust is an honest portrayal (albeit literal exaggeration) of idiosyncratic grief. Inspired by Shawn’s own spiritual abyss after losing his mother to cancer ten years ago and the emptiness he feels at her grave, he created a character in Shmuel who is driven to act on thoughts the rest of us bury.

Unlike Shmuel, Shawn was raised a Reform Jew and free to develop his own religion of, to quote his director’s note, “tolerance with regard to those who question religious values and traditions, the ways in which we contend with our cultures of origin, the right to self-determination and personal meaning…and the ultimate mystery of things both faith and fact.” While Shmuel helped Shawn put his grief into words, To Dust offers acceptance to the Shmuels of the world who find themselves in any kind of doubt. Read Shawn’s beautiful account of his Hasidic self-education here.

Bruce Springsteen, my favorite preacher and dare I say one of Shawn’s, gives a moving soliloquy on soul in his Broadway play, calling it a “stubborn thing.” To Dust proves Bruce’s theory. Every time the movie ends, just before the credits roll, Shawn’s late mother gets the last word with the dedicatory, “For Linda Snyder.” Every time he’s asked about the origins of the film, he gets to speak about his mom. The woman who gave birth to his life has now, as muse, given birth to his career. At the same time, she’s helped soothe his grief and assert her own stubborn soul. I’d call that a supermom.

Shmuel’s twin boys Noam (Leo Heller) and Naftali (Sammy Voit) and his mother (Janet Sarno) who work together to keep Shmuel from veering irrevocably off course.

On To Dust’s journey Shawn has shown friends and family what it means to make a million-dollar feature film with a wildcard story, A-list talent, and luck bordering on kismet. At the two Q&As I’ve attended, Tribeca and the 92nd Street Y, “Team Dust” looked proud and pleasantly surprised, as if they’re still absorbing the film’s success. It had punched above its weight (livestock, cemeteries, rain machines, none of these are for the million-dollar film) and presented ample opportunities to quickly decompose under the Staten Island sun. Broderick, mostly quiet, has made a point of speaking about the quality of Shawn-ness that made everyone want to do their best. Röhrig, the star of 2016’s Best Foreign Film Oscar winner for Hungary’s Son of Saul and who prepared for his role for more than a year, has nodded in agreement. To know Shawn is to know exactly what they mean.

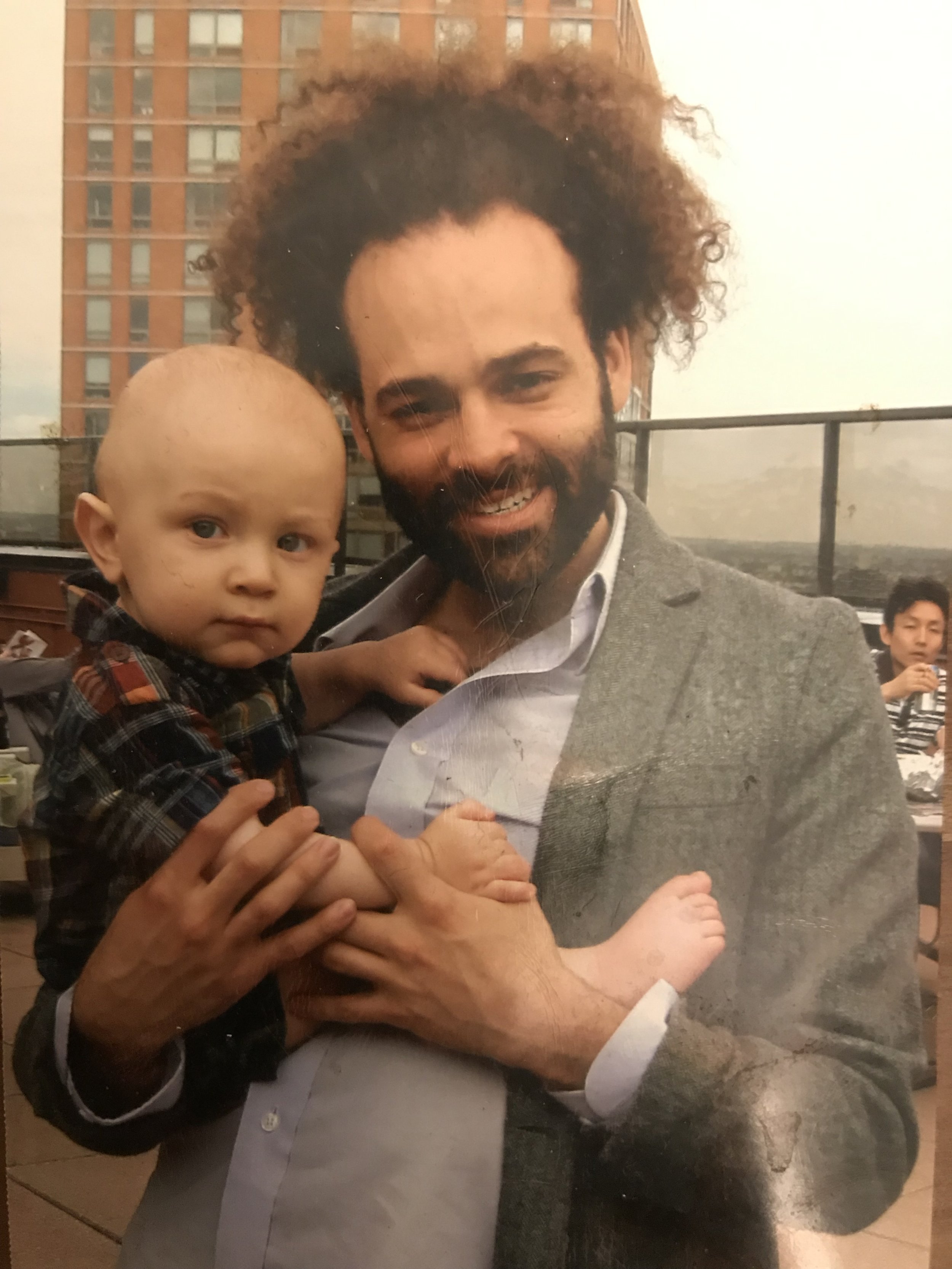

How did I come to befriend this fine sooth-seeker? In 2005, between his first years at Harvard, Shawn interned on a film my future husband was producing. Five years later, after a stint as a promising singer-songwriter (just yell at Alexa, she’ll play him for you), Shawn wanted to move to New York for film school and needed a job. We only had one position open: manny to our new baby boy. Having never changed a diaper ourselves, our bar wasn’t very high, and we believed in Shawn’s basic skill set. I think at this point we would all agree that babies are harder than the Ivy League…but maybe not than making movies.

Our first Mother’s Day with 11-month-old William.

Our chosen-family friendship grew sweeter as we subsequently fell in love with Shawn’s partner and ideal reader, Michele Paolella. The circle was completed in 2015 when, alongside the early momentum of To Dust, Shawn, Michele, Bret, myself, and William welcomed baby girls into the world, besties from birth.

Now over 90% critic- and audience-praised on Rotten Tomatoes and playing in more than two dozen theatres nationwide, my next personal To Dust milestone will be taking William downtown to the movies, where we will sit back and watch the big screen illuminate with the soul of one we love.

William on the Staten Island set of To Dust, “guest directing” part of the road-trip scene. 2017.