HAVE A THINK

On Monday night, September 10, 2018, I delivered the following talk for the launch of my grandfather's book, Alcoholite at the Altar, at Zenith Bookstore in Duluth, Minnesota.

Thank you all for being here tonight to learn more about the work of my late grandfather, Roger Forseth, who dedicated his career to the study of addiction and literature. I am so happy to finally be celebrating the launch of our book: Alcoholite at the Altar.

Thank you Bob, for your hospitality, and for bringing your beautiful bookstore to Duluth. A bookstore we wouldn't have immediately known about if not for my resourceful aunt, Ellen Pioro, who led us to the newly opened Zenith after my grandfather passed. I believe we contributed some 50 boxes of Grandpa's "extra" books to these shelves and it would have made him so happy to have a piece of himself in this special place.

Bob Dobrow, owner of Zenith Bookstore in Duluth, Minn., gives me and my family a most generous introduction.

I would like to thank my mother, Tina Johnson, my grandfather's favorite proofreader and now mine. Not a week goes by that I don't send her a piece of theatre or beauty writing for a "quick proof," as if there's any such thing. She always makes it better.

Last but not least, my grandpa's best friend, Dave Lull. Retired librarian doesn't begin to describe the role Dave plays in the English-speaking world. He supports many famous and non-famous writers, including this one, with his voluntary research. He was instrumental in fact-checking this book and turns out has quite a knack for PR. He was my grandpa's favorite company up to his last weeks of life, is an invaluable friend to my family, and is one of the most beautiful new-old friendships of my adulthood.

Just prior to our event, Dave found a book of Grandpa's that we had donated, Young Eliot: From St. Louis to The Wasteland, with a handwritten reference to me inside. I bought it back.

I was aways somewhat obsessed with my grandfather. He and Grandma were so good to me, and introduced me to the best side of life: The Mall. I'm half kidding—maybe once a month we'd head over the bridge from Superior to Zenith City. My mom and grandma would go shop; he and I would segment off to Mr. Bulky's candy shop and B. Dalton bookstore, where he would always buy me a new book. Whether I chose Anne of Green Gables or Sweet Valley Twins, I appreciate that he never judged.

After I went away to undergrad in Kalamazoo, Michigan, we would meet up in Chicago. My favorite visit was for an MLA Convention where we heard Tom Wolfe speak and I met Robert Fagles, the late great Greek translator, in the elevator. Over the years Grandpa sent me all his articles—to Kalamazoo, France, Santa Fe, even one on O'Neill when I was interning Off Broadway that I shared with Michael Emerson, of Lost and Person of Interest fame. Michael was going into rehearsals with Kevin Spacey for an Iceman Cometh on Broadway and promised to share the piece with Spacey who I like to think read it between his other activities...

Fast forward to the spring of 2014. Nearing 87, Grandpa sent me a most exciting email. It read:

Dear Cassie, Bret and William,

I'm forwarding an email on the digitalizing of Dionysos. It's clear that there is a felt need for the magazine, which both surprises and pleases me. I'll be interested to see how much it will be used.

I have another idea: I'd like to form an e-book out of my various essays and papers that I've published over the years. It would consist of the pieces on addiction and literature, essays on Sinclair Lewis, and other related publications. Would you edit, Cassie? I've got all the publications here (you must have quite a few of them) and they should add up to a substantial volume.

What do you think?

Love,

Grandpa

I responded that I would be ecstatic to do this (as if it would be easy) to which he adorably replied:

Thank you, Cassie, thank you. We might pull this off!

Little did I know that turning hundreds of pages of old printouts into new book form would take four years from the time of that email. It truly killed me not to have the published book in his hands when he passed away in December of 2016. I was able to show him our cover but the interior took another year+ to clean up as my mom, Dave and I vetted scanning errors, and I contended with the limitations of Word. The lessons for any aspiring bookmakers: 1) Sometimes it's easier to start from scratch than try shortcuts. 2) Never, ever design a book in Word.

But here's the fun part: as I started to re-read my grandpa's articles with an eye to the eventual book, I was astounded by the clarity of his insights, the beauty of his prose, and the breadth of his reading. A look at our 33-page index will show you the literary knowledge base Grandpa was drawing on.

For the introduction to this book, I had planned to get one last article out of Grandpa. When he passed away before we reached that point, it took me six months to figure out what I wanted to say. I would like to now share a few excerpts from the book starting with this from my intro entitled, "Half A Brain Is Better Than None":

This title, “Half a Brain Is Better Than None,” was reserved for the memoir [my grandpa] never wrote. It refers to the doctor’s diagnosis after seizures brought on by alcohol withdrawal indicated that “half his brain” would never return. It amused him to share this extreme, and mercifully inaccurate, forecast (my grandmother less so), as it was only in sobriety that the whole of his brain became exercised. For it took quitting drink and digesting the experience to focus his brainpower on what would become the thesis of his life: to study the writer and addiction.

While my grandfather did have a memoir-worthy life, a life that tells a rich American and human tale, there could be no better autobiography than these essays, a tribute to writers he loved and a glimpse into his great mind. Most revelatory was his posthumous and imaginary relationship with Sinclair Lewis, a complicated and tragic man whom my grandfather was uniquely suited to understand, and who dearly needed understanding. With Lewis, he shared Minnesota, where Lewis was born and my grandfather attended college before spending the majority of his career across the bridge at UW-Superior. They shared a love of letters, of driving, of drink (unfortunately at times the two at once), of pastime turned to habit to disease. They shared their wives’ first names (Grace), a certain physical insecurity, and, most importantly, a Romantic view of life as meant to be, well, drunk—but in a Whitmanian sense all too easily confused with the Dionysian. So too did they share a literary palate that had room for the styles of Thoreau, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Joyce, some of whom dealt Lewis harsh blows for his achievements in naturalism over experimentation. They differed in fame, family, and demise—my grandfather quietly taught and wrote, recovered from his addiction, and got to enjoy being a husband, father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. Lewis, not so.

Lewis died in 1951, but my grandfather wouldn’t focus on his writing for many years. After the births of four children, several teaching posts, and the successful completion of alcohol treatment, he connected with Lewis from the vantage point of one who had shared his disease, lived to tell, and was determined to understand. I imagine that, were he more evangelical, my grandfather would have loved to go back in time and meet Sinclair Lewis, not only as a fan but as a friend, an A.A. sponsor, a fellow alcoholic—an understanding that, recovering alcoholics say, is their greatest bond of all.

LET'S HEAR FROM ROGER

In 2016 at age 89 and sober for 42 years, in the last "semester" of his life my mother and I had separate conversations with Grandpa and each took down a couple quotes that I wove together for the book:

“The only question I had to answer was do I want to live or die. Of course I wanted to live, and everything flowed from that answer. And you stay with it the rest of your life. It’s not fear, it’s a practical matter. It’s not the alcohol in your system, but what it represents in your mind, and the destructiveness of it. My life changed so much and so much for the better after I quit drinking. The problem with alcohol is essentially a philosophical problem. I started writing about this late—I wanted to wait until I had something to say...until the alcoholism experience had penetrated my theoretical mind. It had to be experienced first, then rationalized so that I could objectify and write about it, years later. I remember the moment when I realized I had to write, after reading Mark Schorer’s biography of Sinclair Lewis—that was the revelation, that I knew I had something to add.”

My grandfather quit drinking at age 47 in 1974 and I know that's when he feels his life began. Approximately ten years later, in 1985, he published the pioneering article Alcoholite at the Altar, from which I'd like to share a few thoughts:

The subject of alcoholism and the writer—especially the twentieth-century American writer—has received massive anecdotal attention, but little serious analysis. Critics cite with apparent approval an article by the psychiatrist Donald Goodwin: “Alcoholism is unevenly distributed among groups. More men than women are alcoholic, more Irishmen than Jews, more bartenders than bishops. The group, however, with possibly a higher rate of alcoholism than any other consists of famous American writers” (86).

Forseth goes on to say:

I wish to emphasize strongly, however, that it remains to be seen whether drink is necessarily bad for art—even where the artist is a compulsive drinker. A distinction must be made between the devastation of personal lives and the realizations of art. Dick Diver in Tender Is the Night and Julian English in Appointment in Samarra and the Consul in Under the Volcano are marvelous creations that could only have been drawn by alcoholics. The personal calamity is sublimated into the positive creative act; in Edmund Wilson’s words, the “victim of a malodorous disease which renders him abhorrent to society and periodically degrades him and makes him helpless is also the master of a superhuman art which everybody has to respect and which the normal man finds he needs” (“Philoctetes” 240)...Wilson’s observation helps to keep matters in perspective by focusing on the serious art, not the sensational life. Truman Capote once said, with his characteristic exaggeration, that “I don’t know a single writer…who isn’t an alcoholic” (Dunham 29), but more revealingly he also wrote, “I’m an alcoholic. I’m a drug addict. I’m homosexual. I’m a genius” (261). Capote’s stylish anguish epitomizes the problem before us.

The article concludes:

Sinclair Lewis died of drink. He lived his life in a state of unresolved alcoholism. For that illness no one is morally accountable. He did not “used to be a drunk.” He was always a drunk. This central fact must be accepted—accepted not with contempt or derision but with sympathy, indeed with the scriptural sense of charity; but it must be accepted. Only then can one see Sinclair Lewis as he really was; and from there, one is tempted to add, his literary achievement as it really is.

I would like to briefly quote Chapter IV, dedicated to Hemingway, for its glimpse into the marrow of how my grandfather passionately felt that addiction should be studied:

There is another area where it is necessary to be aware of the phenomenon of co-dependency. “Hemingway inspired a series of seventeen personal memoirs,” notes Meyers (568): seventeen 'co-dependents'...for that is how these documents must be read. A sensible application of knowledge about co-dependency is, I urge, a precondition to the examination of these documents by a serious biographer or critic...It is not a simple matter to be an alcoholic, nor to be called one, nor to live with one—nor to write about one.

What I most emphatically do not recommend to scholars is the application of a theoretical conception of the nature of alcoholism to the writing of biography...in the manner of Marxian or Freudian analysis. Alcoholism is not an ideology; it is a disaster, and a disaster that manifests itself in myriad forms. But a firm grasp of the nature of alcoholism, of how it works its devious ways into the most ordinary aspects of the human condition, can serve as a useful explanatory tool.

In one of my favorites, Chapter V, the piece I mentioned on Eugene O'Neill, Grandpa includes a quote by William James: “Half of both the poetry and the tragedy of human life would vanish if alcohol were taken away.”

This is the perfect conversation starter for what feels like the elephant in the room...what some might call a buzzkill...and part of the journey that Alcoholite will take us on. If the first half of my life was informed by temperance, after alcohol was all but banned from my family following my grandfather's treatment...and my uncle's...and my dad's, the second half's been influenced by the ubiquity of alcohol on college campuses, in the theatre, in restaurants. The fact that another book I am working on is a cocktail book for my husband's restaurant sums up the dichotomy of this conversation and my life. After what my grandparents went through, my grandmother wished that no one would drink and did not think anyone could do so in moderation. I think we know the latter isn't true but for my grandpa, who was less concerned with others' habits, this was simply his story. Wherever readers are in their comfort level with drink, Alcoholite invites greater self-awareness regarding intoxication. And most comfortingly to the reader in recovery or struggling with addiction, I say, You can't find better company.

A word on my grandma, Grace Bahr Forseth. As a working parent in direct daily competition with my husband for time to meet our many goals, I want to point out that my grandparents met at Carleton College as English majors, as equals. She could more than keep up with him. They went on to have four children, she stayed home, he worked, they both drank. After they sobered up and my grandpa began publishing, she applied her writing and editing skills to the improvement of every page he wrote. He thanks her throughout—he wasn't a fool—but I would not want to have her influence nor her intellect under-acknowledged here today.

My grandpa was a reader before he was a drunk, and this is a book for literature first, addiction second. It is also an ode to Sinclair Lewis, Minnesota and American writers, from someone whose favorite writers were Shakespeare and Keats, and whose dissertation at Northwestern centered on the poetry of William Blake. It's a story about home and running away, by someone who turned down his father's lucrative business for a life in letters, and largely about someone, Sinclair Lewis, who bounced between Minnesota, New York and Europe all his days. It's a book that explores the nature of alcoholism in a far more exhaustive way than I can touch on today.

The last excerpt I'll read is fittingly Minnesotan and from Chapter IX, A Romance of Manners and Class, on Sinclair Lewis's novel Free Air:

Lewis, with precision and considerable wit, re-creates much that I for one experienced growing up in South Dakota during the Depression. One example will have to suffice. The heroine Claire Boltwood and her father are motoring through Minnesota and stop for lunch at Reaper, where they “encountered a restaurant which made eating seem evil”:

It was called the Eats Garden. As Claire and her father entered, they were stifled by a belch of smoke from the frying pan in the kitchen. The room was blocked by a huge lunch counter; there was only one table, covered with oil cloth and decorated with venerable spots of dried egg yolk. The waiter-cook, whose apron was gravy- patterned, with a border and stomacher of plain gray dirt, grumbled, “Whatdyuhwant?” (74)

Forseth seconds Lewis:

In 1935, on a trip from Aberdeen to Seattle aboard a Chrysler touring sedan, our family stopped at the only café in Lemmon, SD for dinner. My mother, knowing what Lewis knew, demanded to inspect the kitchen before we ordered; it flunked, so on to Hettinger we went, where we were at least not poisoned. I have made that trip many times since, and can report that Lewis’s 1919 description is still as accurate as it is vivid.

There are several moments in the book where my grandfather's personality shines through, and it's wonderful. Alcoholite is a literary tour and as I make my way through some of the titles I haven't read, I experience them as if through my grandpa. This year I read Babbitt and there were moments where I could hear him roar—or rather silently shake, the way he laughed.

In conclusion I'd like to share the end of my intro:

My grandfather used to be struck with something that my grandmother kindly coined “spells.” They came at times when he was over-stimulated and having a bout of Stendahlism—a term I apply to endorphin-induced anxiety—such as during the excitement of our opera and dining excursions to Chicago. Or he might struggle if socially trapped, such as by a houseful of raucous family when he was over people and ready for a book. For the person without a drink in hand, escape is a different word.

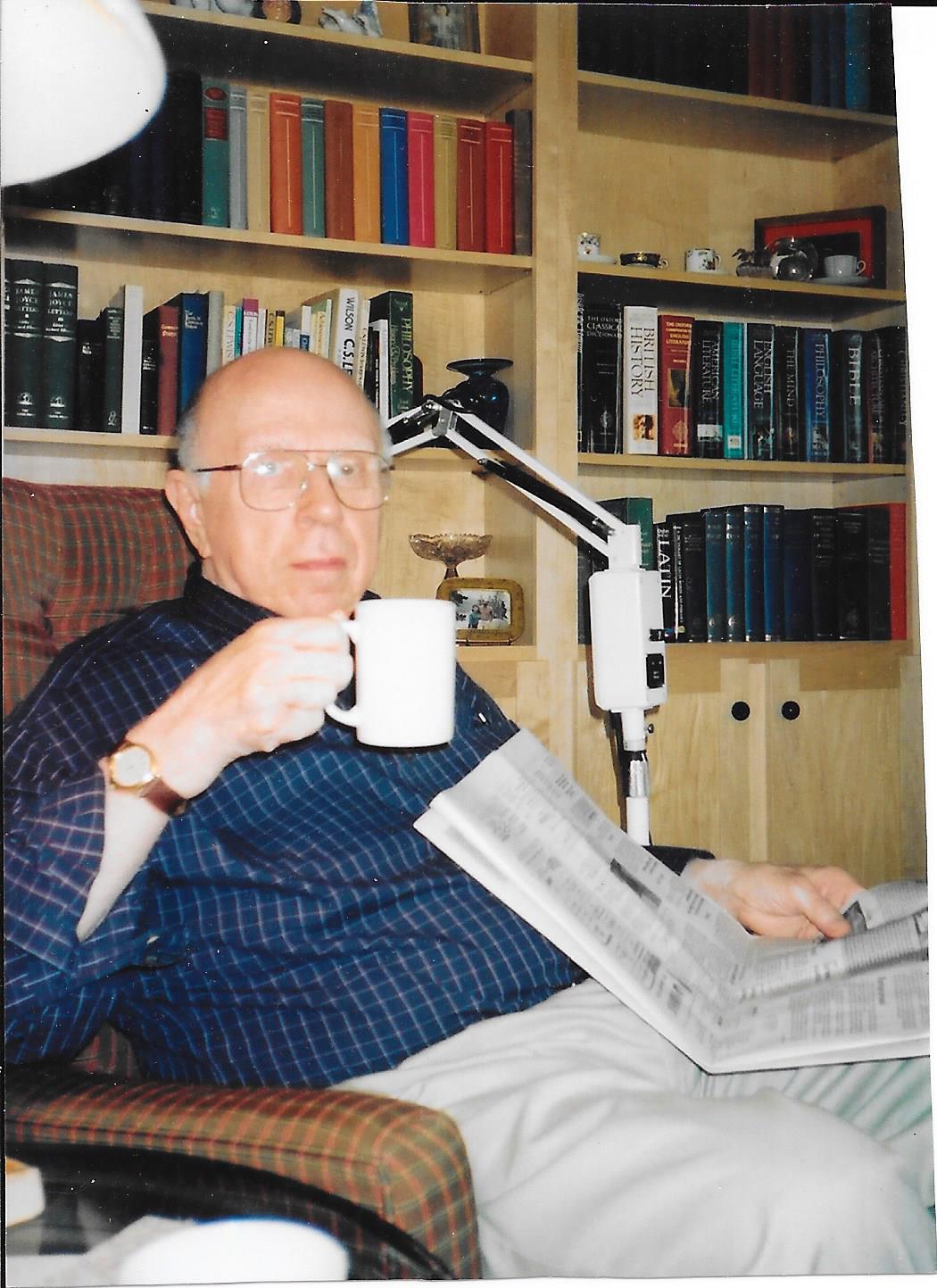

I find it heroic that my grandfather managed and endured these spells for so many years without recourse to the bottle. Modern life makes it hard to do like Socrates and aphistemi (“stand apart”) when one needs to have a think, as the philosopher so memorably does between the drinking bouts that bookend Plato’s Symposium. But Grandpa got good at retreating to his room, cancelling plans if necessary, and working through, or waiting out, his disturbances.

It’s been a couple of decades since those joyous Windy City trips with my favorite people. Two children come and both grandparents gone, I continue to be educated by my grandfather, ever the teacher, through these pages.

With that said I'd like to thank you, Grandpa, for sending me that email and for your most recent lesson: teaching me how to make a book. May we now and for a long time to come raise our reading glasses to Roger Forseth, and #HaveAThink.